When it comes to renewables, there's no denying that China is thinking big and moving fast.

Venture funded-eSolar signed a multi-billion dollar agreement last week to build 2 gigawatts of solar thermal power plants of the "power tower" variety in China. ESolar will provide expertise and technology in this "master licensing" agreement according to a press release. (See eSolar Lands Whopper Contract).

This announcement comes a few months after First Solar signed a similarly large-scale agreement with China for thin film PV panels.

But take these announcements with a grain of salt. These deals have multi-year if not multi-decade timelines and they are more technology transfer agreements than strict purchase orders. And with regards to solar thermal, China may not be the best place on earth to install that particular technology - too little direct sun, too little water, and geographical issues make CSP a stretch in China.

Allow me to share an anecdote about PV agreements in China related to me by a friend at Suntech.

The People's Republic of China has about 33 Provinces (34 if one counts Taiwan). And each one of these provinces has invited the founder of Suntech, Dr. Shi Zhengrong, to an elaborate signing ceremony replete with speeches, gifts, and plaques. The province pledges to install 2 gigawatts of solar, food and beverages are consumed and then Dr. Shi returns to his factory to build more panels to ship to Germany and the U.S.

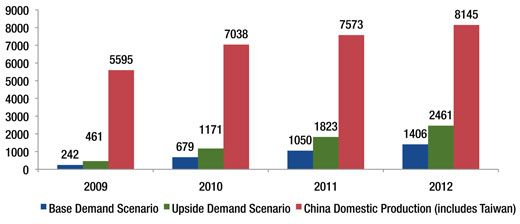

The point is - despite the enormous potential, there is very little action in China's domestic PV market. A fraction of China's PV capacity is deployed domestically according to the demand data from GTM Research's PV in China report. Note that the units are "MW."

So what will it take to rev up the Chinese domestic solar market?

Technology transfer from firms like ESolar and First Solar? Or will it come from another more organic direction?

Perhaps we can look at the rapidly growing Chinese wind market as a model for setting the Chinese domestic market in motion.

The development of the wind industry in China was the country’s first real foray into scaling a renewable, non-dispatchable generation technology. The government’s approach to building this industry -- establishing a subsidy program with grid interconnection and independent power production are good indicators of the way it might approach scaling its domestic solar industry.

China’s wind market was virtually nonexistent 20 years ago, and has grown to be the fourth-largest market in the world, behind the U.S., Germany and Spain. Over the past five years, installed capacity has grown at an annual rate of 52 percent (!). Cumulative installed capacity through 2008 was over 12 GW, with 6.2 GW installed in 2008 alone. China will likely overtake Germany and Spain to reach second place in terms of cumulative installed wind capacity in 2010.

Real progress in China's wind market started in 2003, when the central government administered the first round of the Wind Power Concession Program. Wind concession projects are funded by feed-in tariffs (FITs) that vary by province, depending upon wind resources.

The Chinese government passed the Renewable Energy Law in 2006, and perhaps more importantly, established a Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS) as a part of its Mid and Long-term Renewable Energy Implementation Plan in July 2007. The RPS mechanism includes both a capacity and a generation requirement. The requirements are as follows: The share of non-hydro renewable should reach 1 percent of total power generation by 2010 and 3 percent by 2020 for regions served by centralized power grids.

The program is not without its issues. There is a danger with any capacity-based incentive -- putting the asset in the ground is often more important to the developers than correct and efficient operation. Due to hasty development and disagreements between the developers and the Chinese grid companies regarding interconnection agreements, approximately 3 GW of wind-based capacity remains unconnected to the grid. This represents one-quarter of all wind capacity in China.

As with early-stage solar development in China, wind development has been driven by a concession process in which a specific project is put out to bid. Developers place their bid on a generation basis (i.e. what kWh rate they would need to receive from the government to operate the project profitably for 25 to 30 years). In the early stages of the concession program, pricing was often the main determinant of the concession winner. Large generation companies would bid extremely low kWh prices, effectively meaning the project would run at a loss for its operating life. Generation companies’ primary motivation in winning these concession projects was to meet Renewable Portfolio Standard capacity requirements. As a result, projects were not built according to best practices, and inexpensive components of lower quality were often used. This has resulted in China wind projects having a net capacity utilization factor 10 percent lower than U.S. wind projects on average. The NDRC responded in 2006 by altering the concession criterion, weighting the price as 25 percent of the overall bid evaluation (previously it counted for 40 percent). In 2007, the pricing criterion was changed again, with the median bid used to set the winning price. The government seemed to be giving more weight to factors like turbine quality and developer experience, which had been marginalized in earlier National Level Concession Projects.

The history and process of wind development provides a potential template for how large-scale solar development may unfold. As the wind base plan demonstrates, the Chinese government is prepared to scale renewable development aggressively once the technology reaches a price point that it considers appropriate, and local manufacturers and developers can competently fulfill the government’s growth targets.

The aggressive scaling of wind combined with the potential for solar projects at low concession rates (i.e., $0.07/kWh for wind, $0.16/kWh for solar) means that developers will need large balance sheets to facilitate access to low-cost debt, and will still likely operate at extremely low margins. These factors make it unlikely that any company outside of a government-owned or affiliated developer will be a major player in domestic project development. For foreign developers or joint ventures, it is likely that the only way to make project economics work at current and proposed tariff rates would by selling Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) credits. Even with that revenue stream, margins will likely be very thin.

As renewable policy transitions to national feed-in tariffs, solar is likely to follow a similar course of development.

In the words of Andrew Beebe, Vice President, Global Product Strategy at Suntech, "The PV markets of China and the US actually have a great deal in common. They're both currently benefiting from a great deal of regional and national government support and focus; they are both complex with regulatory and bureaucratic challenges; and they both promise to be absolutely massive."

For a deep dive into the Chinese photovolataic market - check out the China PV Market Development report.