Last week, global delegates gathered in Katowice, Poland to begin another round of climate talks. Negotiators are tasked with finishing a set of rules for the agreement, which they agreed to hash out before the end of 2018. If it goes well, countries should have an agreed-upon formula to increase the ambition of Paris climate commitments in coming years.

We wanted to look behind the technical, jargon-heavy discussions to take stock of where global renewables markets stand. Even in the few years since countries signed onto the Paris Agreement, market dynamics have caused big shifts in global renewables deployments.

While many of those changes are due to improving economics, the climate talks have built confidence in the energy transition from non-governmental organizations, subnational government and corporations.

“Over the years, even in an indirect way, the talks have been really important to catalyzing and stimulating the clean energy economy,” said Lou Leonard, senior vice president of climate and energy at World Wildlife Fund.

Two recent reports from the International Energy Agency (IEA) and Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF) show the energy transition is reaching a new state of maturity even as climate change remains a severe challenge.

Source: International Energy Agency

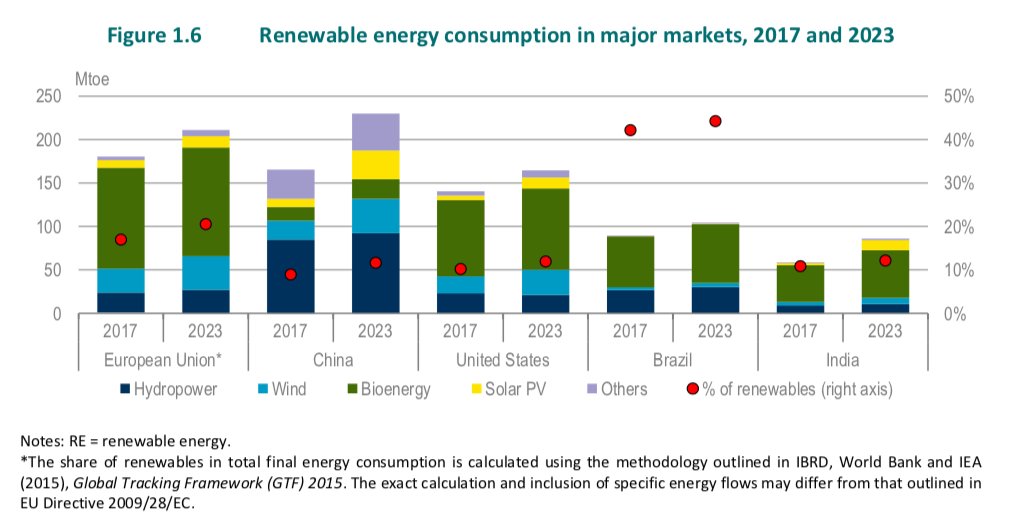

In all major markets, IEA forecasts in its base case that renewables will grow through 2023. While bioenergy leads much of that growth, wind and solar play significant roles in bumping the total renewables consumption in countries like China and India.

Those additions will be helped along by increasingly favorable economics.

Source: International Energy Agency

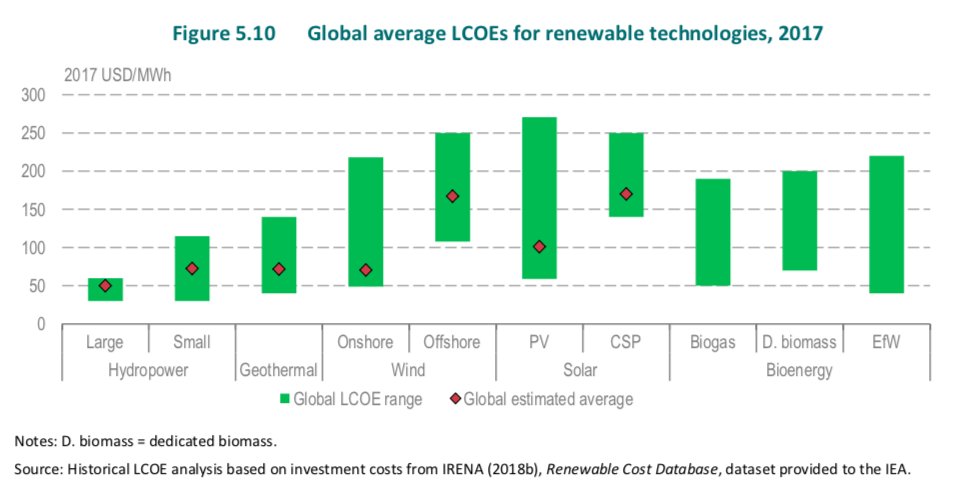

In 2017, the floor for the levelized cost of energy (LCOE) for onshore wind touched $50 per megawatt-hour and PV was near that cost as well. According to IEA, LCOEs for most solar and wind beat out new natural gas in India and China (where gas costs are relatively high). Analysts forecast that offshore wind prices will decline 40 percent over the next five years, while onshore wind declines 6 percent and solar prices drop by a quarter.

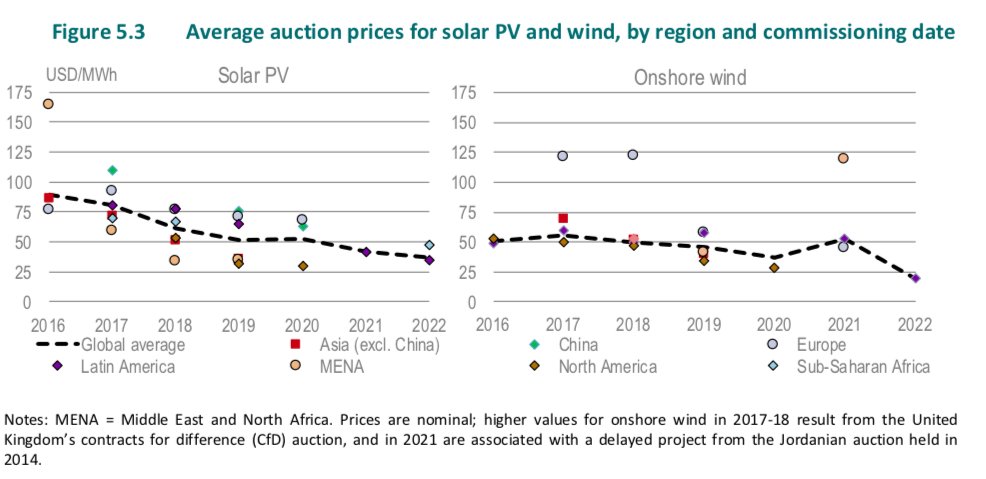

The agency also noted that LCOE isn’t the only way to assess competition. Auction prices are often lower.

Source: International Energy Agency

Auction prices are expected to continue falling through 2022, driven by increasing competition. With solar PV prices currently hovering as high as $75 per megawatt-hour in some markets, the global average for solar drops to just above $25 per megawatt-hour in less than four years. Onshore wind will be even cheaper, likely below $25 per megawatt-hour by 2022.

With those positive trends, lEA suggests the total percentage of renewables in energy consumption will reach 18 percent by 2040.

Source: International Energy Agency

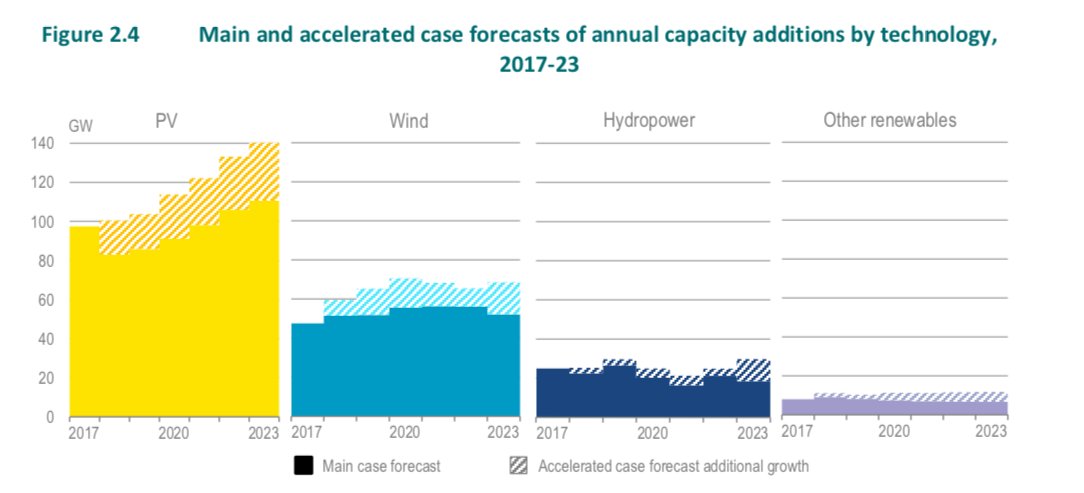

In an accelerated scenario, with more effective policies and market designs, IEA suggests its forecast could increase by 25 percent. For solar, that means up to 140 gigawatts of capacity additions in 2023. Wind additions would be more modest, reaching about 70 gigawatts a year.

But even the accelerated case would not meet what’s required according to a recent report from the United Nation’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. The agency said renewables would have to produce 70 to 85 percent of electricity by 2050 to keep warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius.

According to the IEA, because energy accounts for 85 percent of global emissions, “meeting the long-term objectives of the Paris Agreement means fundamentally changing the way we produce and use energy.” IEA data released during the climate talks showed that emissions from energy fell by about 3 percent over the last five years. But overall emissions from wealthier countries rose for the first time in five years.

“Our data shows that despite the strong growth in solar PV and wind, emissions have started to rise again in advanced economies, highlighting the need for deploying all technologies and energy efficiency,” said Dr. Fatih Birol, IEA’s executive director, in a statement. “This turnaround should be another warning to governments as they meet in Katowice."

Whether countries agree in Poland to ratchet ambitions upward will directly influence their ability to spur the emissions cuts necessary to slow climate change.

Follow the leader

The differing obligations placed on developing and developed countries have long been a source of tension at global climate talks.

Developing countries have asked for more economic support from wealthier countries to help them adapt to climate change. They’ve also suggested that more developed countries, which have caused the most climate change, set aggressive targets that account for historic emissions. Wealthier countries have been slow to come up with the cash and have often chafed at requirements.

Those conflicts have been felt in Katowice, too. As climate talks kicked off, Turkey looked to change its distinction from industrialized country to developing country, which would allow it access to more climate adaptation funds.

Those dynamics aren’t necessarily influencing clean energy development, though, according to recent data from BNEF’s November Climatescope report. The report, which ranks the potential of the clean energy transition in emerging markets, shows that parties classified by the U.N. as “developing economies” are now leading the energy transition. BNEF also ranked Rwanda, part of the U.N.’s “Least Developed Countries” group, in the top five emerging markets.

“Just a few years ago, some argued that less developed nations could not, or even should not, expand power generation with zero-carbon sources because these were too expensive,” said Dario Traum, a BNEF senior associate and the Climatescope project manager, in a statement. “Today, these countries are leading the charge when it comes to deployment, investment, policy innovation and cost reductions.”

BNEF points to countries including China, India, Chile and Brazil as those ahead on the clean energy curve. That trend is reflected in IEA data as well.

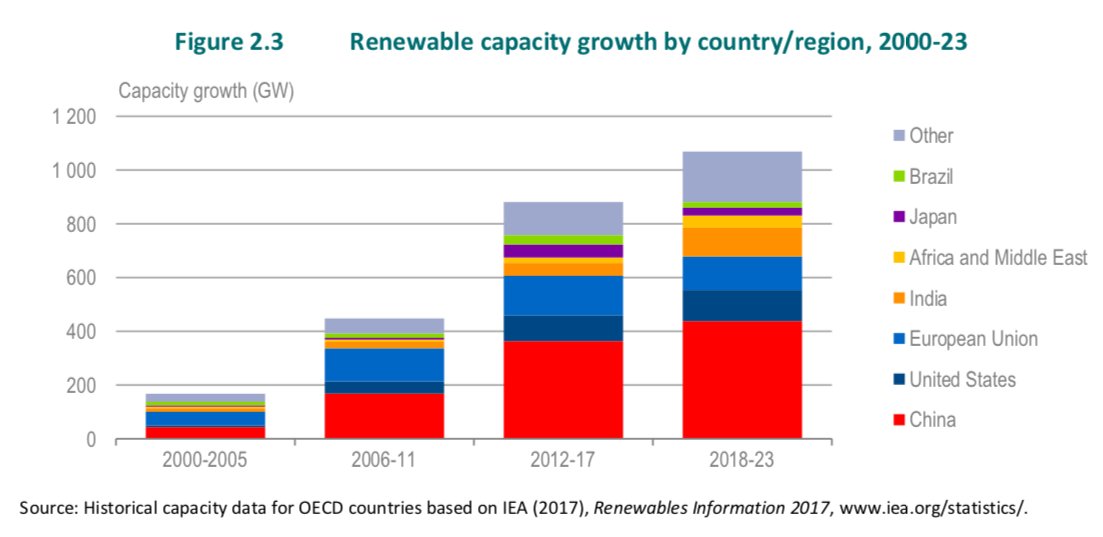

Source: International Energy Agency

Between 2016 and 2017, China staked out its position as a leading clean energy market. IEA forecasts that leadership will continue through 2023, with countries such as Brazil and India also making notable contributions.

Through 2023, IEA forecasts that China will account for as much as a third of capacity growth. It will be the largest distributed generation market through 2023, with the industrial sector accounting for much of that growth.

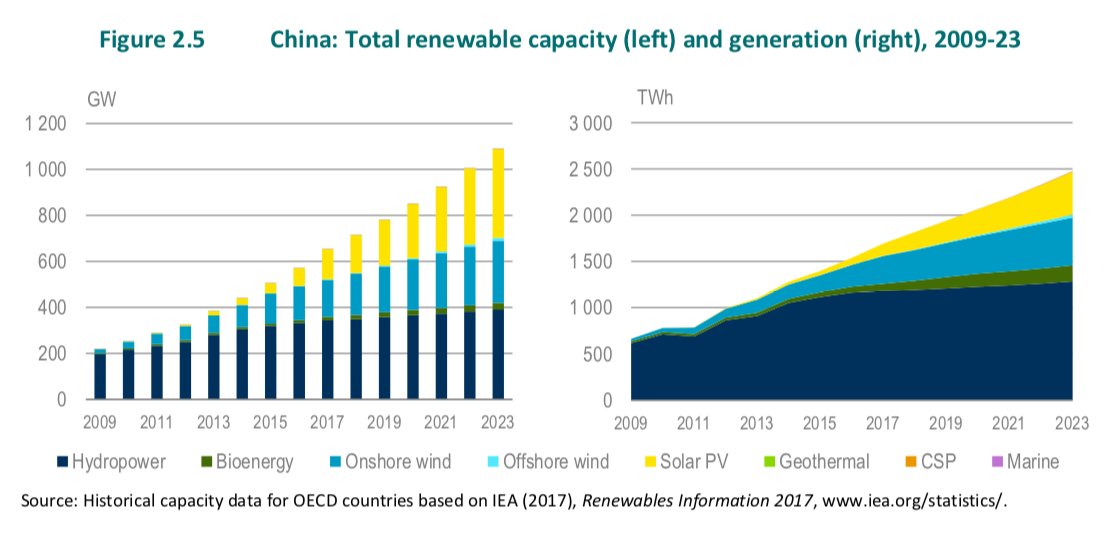

Source: International Energy Agency

In its base case, IEA projects China will add 283 gigawatts of wind and 386 gigawatts of solar by 2023. BNEF agreed that China will maintain its dominance among clean energy markets for “years to come” despite difficulties in its market this year, namely, the end of subsidies and renewables curtailment that benefited coal generators.

In an accelerated case, IEA forecasts that China could add an extra 53 gigawatts: 17 gigawatts in wind and 36 gigawatts in solar. That accelerated case relies on faster approval for offshore projects, an expansion in transmission and accelerated cost reductions for utility-scale solar projects.

China’s leadership in clean energy means it will also be a leader at this year’s climate talks. At the same time, its distinction as the world’s largest emitter and a major coal producer means it's coping with conflicting interests.

Countries including Mexico, Chile and Brazil are also experiencing notable capacity increases through 2023. In Mexico, distributed and utility-scale solar will dominate growth, adding 16 gigawatts through 2023. BNEF named it as a top emerging market.

Chile gained the distinction as the top scorer in BNEF’s report because of strong clean energy policies and its commitment to decarbonization. Currently over half the country’s electricity comes from fossil fuels, but BNEF notes that there’s a good amount of short-term opportunity for clean energy there.

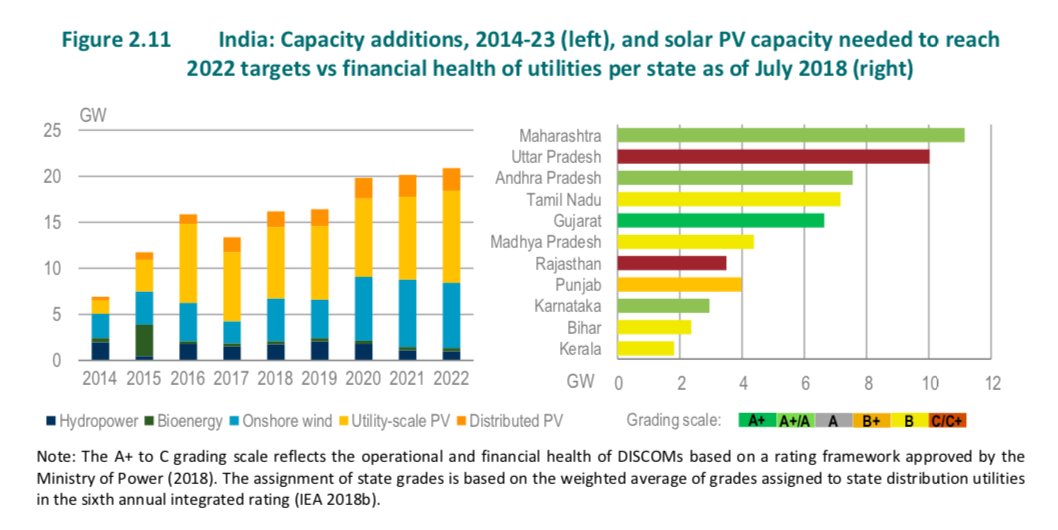

India offers yet another example of a developing market making significant strides. IEA’s report projects that India’s renewable energy forecast will double in the next five years, growing by 107 gigawatts.

Source: International Energy Agency

BNEF ranked India second in its overall Climatescope scorecard, based on the country’s competitive auctions and ambitious renewables target of 100 gigawatts of solar and 60 gigawatts of wind by 2022. In 2017, BNEF notes, India contracted more than 10.5 gigawatts of solar.

But the country is also facing some headwinds. To prepare the grid for higher renewables integration, IEA said India needs to work on forecasting systems and using flexibility from thermal power plants as well as demand response and storage.

IEA also notes that only a few of the country’s distribution companies are on good financial footing and about 40 percent of solar capacity additions through 2022 are slated for areas with low financial performance.

Compared to China, India’s portion of global emissions is small: 4.64 percent compared to about 26 percent (data released this week noted that emissions in both countries are growing, and both countries ranked among the top 10 emitting countries in 2018). But India has been a high-profile negotiator in international climate talks, leading calls for more money from wealthier countries and jamming news cycles with ambitious solar targets and alliances.

India looks to be framing its role similarly this year: The theme of the country’s onsite pavilion is “One World, One Sun, One Grid.”

Maturity or meltdown?

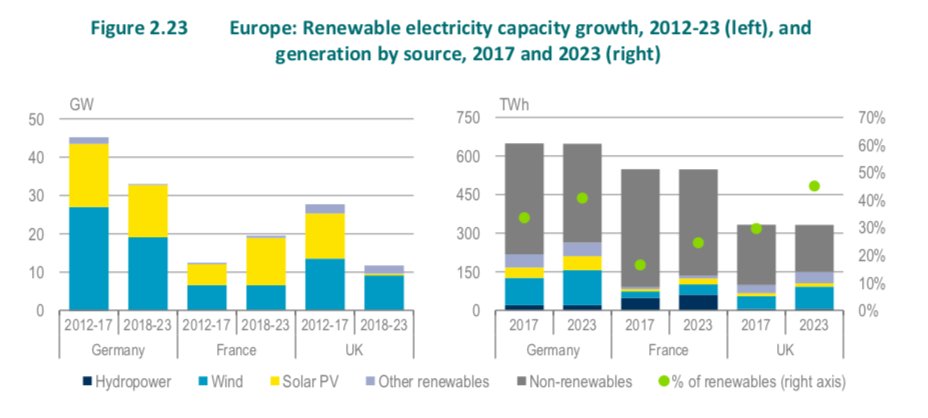

Though BNEF notes that developing countries are now leading the charge, Europe still lays claim to a great deal of clean energy growth.

IEA revised its forecast up from last year and now projects an added 144 gigawatts of capacity in the region, 68 gigawatts in wind and 59 gigawatts in solar. That growth, adding about 25 percent to current capacity, is still lower than the past six years according to IEA — an indication of those markets partially ceding dominance to the likes of China and India.

Source: International Energy Agency

Through 2023, half of that European growth will come from Germany, France and the United Kingdom. Those countries are slated to add 33 gigawatts, 19 gigawatts and 12 gigawatts, respectively.

Though Europe’s growth through 2023 is 20 percent lower than in the previous six years, the region will maintain its consistent growth due to policy levers associated with 2020 climate targets. European countries are also expected to revise their targets upwards, increasing ambitions in line with the Paris climate agreement.

Discussions at Katowice will help decide how significantly those targets increase. Ahead of the talks in Poland, the EU proposed a plan for a greenhouse-gas-neutral economy by 2050. So far only part of the bloc, including countries such as Sweden, the Netherlands and Denmark, is on board.

The United States’ more mature market is also flagging somewhat. IEA revised the country’s outlook down by 6 percent, a total of a slight 7 gigawatts, in part due to changes in U.S. policy, trade and federal tax rates.

The agency still expects the U.S. to add 116 gigawatts through 2023, an increase of 44 percent. The United States will also still rank within the three largest growth markets, behind China and the European Union. But tariffs on steel and solar modules — despite a temporary truce — as well as policy changes, like the reversal of the Clean Power Plan, mean renewable technologies face national challenges rather than national support.

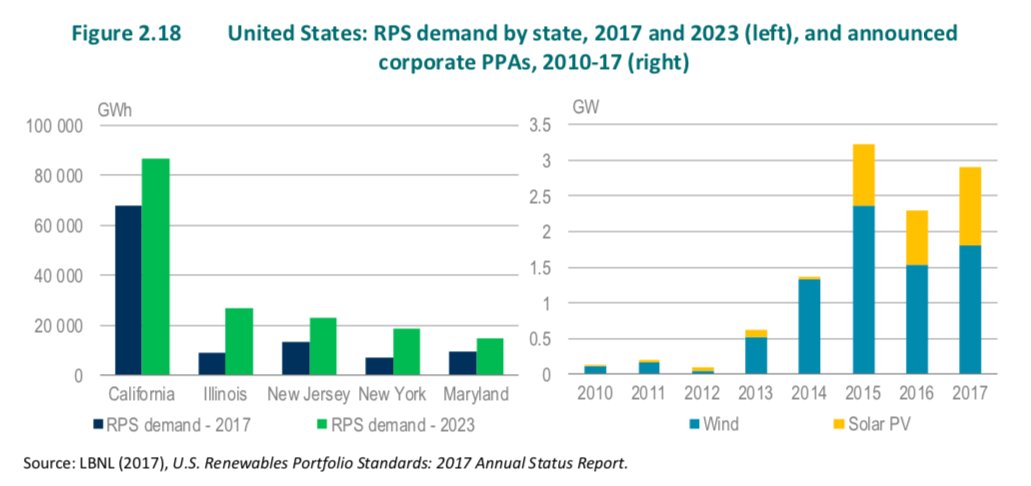

In the absence of federal leadership, state policies will become a driver of growth.

Corporate procurement plans, with large companies looking to acquire large amounts of renewables, will also mean gigawatts added in the coming years.

Should the U.S. be able to hit its upside potential, IEA forecasts that renewables could grow by an added 22 gigawatts. But the agency cautions that will be difficult without the policy pressure from the Clean Power Plan and the added incentives offered by tax credits expiring in 2020 and 2021.

U.S. cooperation was integral to the compromise that brokered the Paris Agreement. Now that President Trump has said he’ll pull out of the pact and the U.S. relationship with the international climate community has grown tense, it could become more difficult to get countries to commit when one of the world’s wealthiest won’t. America's stance has become a stumbling block in negotiations, when the country, along with Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Russia, objected to fully recognizing the takeaways of the IPCC's bombshell report — a report that was commissioned during a 2015 climate conference.

Leonard at World Wildlife Fund recognizes “there’s a lot of ways in which the U.S. administration is really not aligned with the momentum that we’re seeing around different aspects of climate action.” But he also said the sway of subnational leaders and U.S. corporations shouldn’t be underestimated. Efforts like RE100, through which 158 companies have pledged to go 100 percent renewable, will continue to push clean energy expansion in the U.S. and abroad.

Overall, the upside potential is greatest in the world’s largest markets. Should China increase auction volumes for wind and solar and easily transition from feed-in tariffs to renewable portfolio standards, the market could increase its growth by a whopping 38 percent.

The EU may grow its capacity additions by 12 percent, if the region increases auction activities as a response to climate targets and sees a surge in corporate power-purchase agreements.

India, too, shows potential for a further 11 percent growth in an accelerated scenario where its solar auctions pick up speed and project development quickens. The U.S. could see a 10 percent increase if developers can push more projects under the tax incentive deadline and corporates double down on wind and solar PPAs.

A sobering outlook

The rule-making priorities of this year’s climate talks means that fewer grand gestures are likely. But conversations in Poland are essential to make sure Paris commitments are accompanied with rules guiding climate action.

Watchers also say it’s an important time for countries to work out how to ratchet ambitions, including on renewable energy, by the year suggested in the agreement: 2020.

Much growth in wind and solar has been prompted by market forces, corporate sustainability goals and cheaper prices. But discussions in Poland could indicate whether that momentum will continue at a multinational level.

Though renewables markets around the world may be growing, even in the most optimistic markets, integration and expansion remains an uphill battle. In India, for instance, coal still accounted for 75 percent of the country’s generation in 2017.

That trend is pervasive globally, according to BNEF: Though coal capacity additions in 2017 fell to a decade low, coal-fired generation actually rose by 4 percent last year. Natural gas generation increased 3 percent.

And while renewables have successfully moved into electricity markets, they’re still relatively new to high-emitting sectors like heavy industry and transport.

Results of IEA’s most recent World Energy Outlook are also grim. A catalog of existing and under-construction energy infrastructure would account for about 95 percent of all emissions allowed under international climate targets, according to the agency. IEA’s Birol said that requires a drastic uptick in renewables.

“If the world is serious about meeting its climate targets, then, as of today, there needs to be a systematic preference for investment in sustainable energy technologies,” said Birol.