2009 had plenty of greentech hits: technical breakthroughs, lots of VC and government funding, some interesting acquisitions and a few successful IPOs. But there were also a number of misses. Here's a list:

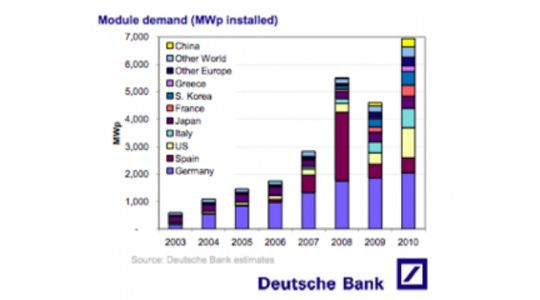

Spain Pays for Its Poorly Executed Solar Subsidy: The mistakes happened in 2008 but the echoes were felt in 2009. Spain went from being the largest PV market in 2008 to almost zero in 2009.

Spain had a lucrative feed-in tariff program that required utilities to buy solar electricity at high rates set by the government. After seeing an explosive growth of solar projects that far surpassed its estimates, the government reduced the solar electricity rates for solar power plants installed after September 2008. Additionally, government investigation uncovered widespread fraud in the administration and roll-out of the FIT program.

A rush to install solar energy systems led to reports of fraud by developers claiming they had finished their projects when they only installed some of the panels or, in some cases, put in fake solar panels to buy time.

Spain had been a great market for Chinese panel makers, who were able to sell their goods at premium prices in 2008. Not so in 2009.

Optisolar Lands Hard: Optisolar had raised more than $300 million based on a vision of the economies of scale of building a gigawatt-sized factory. The vision was that the cost of solar could be radically dropped by building "Solar City" factory complexes capable of churning out 2.1 gigawatts to 3.6 gigawatts of solar cells a year. These factories would cost $500 million to $600 million and be composed of factories-within-factories focused on different tasks: an onsite glass making outfit capable of cranking out 30 million square meters of glass a year; a solar cell unit with 100 identical manufacturing lines; and a full-fledged packaging facility.

In this ideal world modules would cost 0.60 cents to 0.52 cents per watt and fully installed solar power would cost $1.00 to 0.88 cents a watt.

As per Michael Kanellos' article: The ideas from the Keshner NREL paper largely formed the company's business plan.

After building a factory in Hayward capable of producing 30 megawatts to 50 megawatts, it landed $20 million in tax breaks in 2007 to build a factory at McClellan Air Force Base in Sacramento County. By 2011, the million square foot facility would employ 1,000 and put out over 600 megawatts worth of solar panels a year. Although the original paper discussed ways of making cheap solar panels out of CIGS, cadmium telluride or amorphous silicon, OptiSolar focused on silicon because, among other reasons, of its far wider availability.

Plans were also being laid to build an even larger factory after McClellan that would contain the in-house sub-factory for glass making as discussed in 2004.

But OptiSolar didn't stop there. Once organized as a company, OptiSolar also incorporated other ideas for cutting costs. Instead of concentrating on manufacturing solar panels, the company planned on installing them itself (through a subsidiary called Topaz Solar) and selling the power to a utility. By acting as a vertically integrated company performing several functions, the idea was that the cost could be reduced because profit margins wouldn't be split among several companies.

In 2007, it won contracts to install over 200 megawatts in Ontario. The crowning achievement came in 2008 when the company won a deal to build a 550-megawatt solar farm near San Luis Obispo for PG&E over several other bidders. Toward the end of 2008, California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger showed up for a factory opening that 60 Minutes covered.

OptiSolar avoided VCs and won funding from private equity firms accustomed to the long slog of energy deals. Many investors like Robert Puchniak and chairman Geoff Cummings came out of Canada's oil industry.

So what went wrong?

Those closest to the company chalk it up to the credit crisis. When the crisis hit, the company was outfitting the McClellan factory and seeking another $200 million in funding. Prior to the credit crisis, the plan was to hold an IPO in 2010. Others, though, said that the expansive goals seem to be giving the company mission creep. It was negotiating deals for tracts of land while also planning out factories and buying expensive equipment. Besides the already announced deals, it had secured rights to build power plants on 136,000 acres, enough for 19 gigawatts of power.

The company’s failure, ultimately, resulted in the further expansion of First Solar. The relentlessly efficient solar maker bought OptiSolar’s utility and land deals for approximately $400 million earlier this year.

Optisolar was an audacious bet, smacked down by the grim realities of the economy, by mission-creep, and by the hubris of the founders and investors.

GreenFuel Closes Down: GreenFuel Technologies, one of the earlier algae biofuel companies, closed its doors in 2009, a victim of the credit crunch.

"We are closing the doors. We are a victim of the economy," said Duncan McIntyre at Polaris Venture Partners, an investor in Greenfuel.

Although it had raised millions of dollars and landed a high-profile deal with Auranta in Spain to erect test facilities, it could not get money to complete the project. The company had also been chronically saddled with delays and technical problems. The company's plan was to pump carbon dioxide from smokestacks into bioreactors – i.e., sealed plastic bags or tubes filled with algae and water. The algae would grow fat on the carbon dioxide and later be harvested by GreenFuel to be turned into oil for biodiesel.

The firm had raised $13.9 million from VCs including Access Private Equity, Draper Fisher Jurvetson and Polaris Venture Partners.

SV Solar RIP: As one of many solar start-ups destined for the dust bin – SV Solar raised $10.2M from Bessemer to build low concentration PV technology and then quickly disappeared.

Bessemer had funded a low-concentration PV firm (strike one), with a staff that had very little solar experience (strike two), based on some amazing cutting edge technology that they called -- a prism (strike 3). The company’s value proposition was based on the high price of silicon at the time by investors who didn’t fully get the concept of supply and demand -- how the price of the silicon commodity was bound to drop as capacity was added.

2009 to 2011 will see enormous attrition for weak startups in solar power. It will be a gut-wrenching experience but it will leave the industry leaner and stronger in the 20-year solar boom to come.

Some Bad News in Geothermal – Whole Lotta Shaking Going On

Venture Capitalists are accustomed to technology risk, market risk, and policy risk. However they are not accustomed to seismic risk and the possible threat of eathquakes has sort of shut down a project by VC-funded AltaRock.

In September of this year AltaRock’s (Enhanced Geothermal Systems) EGS demo at The Geysers in Northern California suspended its drilling operations due, not to seismic activity, but to the bore-hole collapsing due to unstable geologies. Previous permitting studies had not indicated a problem. AltaRock continues to go after EGS, just not at The Geysers. AltaRock is funded by Google, Khosla Ventures, KPCB, ATV and Vulcan Capital.

But add that PR gaffe to the $9M in damages caused by the actual seismic activity from the EGS project in Basel, Switzerland and EGS boosters are going to have move a little slower and more carefully in 2010.

Failure to Meet U.S. Renewable Fuel Standards (RFS) for Advanced Biofuelse: Under the EPA’s guidelines, refiners are required to blend 100 million gallons of cellulosic biofuel in 2010 increasing to 250MGY in 2011 and 500MGY in 2012. In a recent 1000- page report justifying the advanced biofuel mandate, the EPA outlines 25 pilot and demonstration plants currently operating in the United States. The EPA maintains that in 2010, 100.7 million gallons of cellulosic ethanol and diesel will be produced.

But in looking at the specifics of the EPA’s conclusions, it is interesting to note that 70 million gallons of the 100 million gallons in 2010 is expected to come from Cello Energy – a virtually unknown company that does yet not have an operating website. The company has operated so far below the radar that Paul Winters, the spokesman for a cellulosic industry trade group BIO, was recently quoted as saying, “I have to admit that before the EPA [report], I hadn’t heard of them. I don’t even have them listed on our map of cellulosic facilities."

In recent months, Cello Energy was convicted of fraud and it is unlikely that they are going to be producing meaningful amounts of biofuel any time soon. Cello was run by Alabama’s former ethics chairman, Jack Boykin, and funded by Khosla Ventures, et al.

GTM research forecasts U.S. cellulosic ethanol capacity to reach 28 million gallons in 2010, with 4.4 million gallons of cellulosic ethanol actually being produced in the United States in 2010.

Uni-Solar's Troubles: In early December Uni-Solar (aka ECD) announced plans to cut 20 per cent of its 1900 employee workforce, the latest sign that the company was struggling to weather the economic downturn. The company builds multi-junction amorphous silicon solar cells on flexible substrates.

Like many other companies in the solar industry, Uni-Solar has struggled amid an economic downturn that has strangled investments in building solar power projects worldwide over the past year. Earlier this year, solar panel manufacturers and their suppliers were reporting steep revenue cuts and even losses. Uni-Solar had shut down its factories in Greenville and Auburn Hills for about a month between May and June this year.

While other solar companies began to see a boost to their revenues and profit during the summer, Uni-Solar continued to post losses.

Uni-Solar's product is unique but the reliability and cost model of their technology has been questioned on numerous fronts. According to a recent research note by Deutsch Bank's Steve O'Rourke: "ECD has a solid technology and niche market position, but a higher cost basis and is beset by sharp ASP pressure; when combined with challenging end market conditions (demand and project financing) we expect quarterly losses looking into C2010."

ECD looks to have a challenging 2010.

Smart Grid Backlash: Excerpts from an October 22 article in The Fresno Bee: More than 100 people packed a town hall meeting in downtown Fresno to vent their frustration with PG&E's newest metering technology – SmartMeters – that customers say has led to faulty spikes in utility bills. "The meters, in my opinion, are not very smart," PG&E customer Joe Riojas told Senate Majority Leader Dean Florez, D-Shafter. The meeting lasted four-and-a-half hours. No one spoke in favor of the Smart Meters.

Many customers brought their PG&E bills to show Florez their skyrocketing costs. For example, Don Vercellini of Fresno said his bill recently went from $500 a month to $1,173. "It's straight-out fraud. I want my money back," he said.

Florez complained that the technology for customers to check usage will not be in place for years.

Said Florez: "People don't see the value [in this program]. They just see higher cost, and that makes them angry."

According to Jeff St. John's reporting: Those complaints have focused attention on PG&E's $2.2 billion, 10 million smart meter deployment, with the California Public Utilities Commission demanding that PG&E find a third party to investigate.

But PG&E has already tested many customers' smart meters – made by General Electric and Landis+Gyr and networked by Silver Spring Networks – and have not found any problems with how they're working, according to PG&E spokesman Denny Boyles.

Rather than malfunctioning meters, PG&E thinks the higher bills have come from its two rate hikes in the past 12 months, plus a hot summer that led to many Central Valley residents cranking their air conditioners to beat the heat, Boyles said.

With the feds ready to launch another wave of smart grid funding – it would be helpful for the public to actually want these products and services. And to actually feel some immediate benefit and value from the smart grid. It can't be just about benefits for the utilities.

Imara, Lithium-Ion Battery Firm, Runs Out of Juice: "We have the best product entering the market place." Jeff Depew, CEO of Imara.

In September lithium-ion battery startup, Imara, said it had begun to commercially produce lithium-ion batteries and might have a customer or two to announce in a few months. The company's secret sauce revolved around a cathode that would effectively allow a battery to store more lithium ions than standard lithium-ion batteries. The idea emerged from experiments conducted at SRI in 2000 funded by a program to develop electric cars sponsored by the Department of Energy (see Battery-Maker Imara Shuts Its Doors).

By December, unable to obtain their next round (a problem many mid-stage start-ups are going to face), Imara was closing its doors and ceasing operations. The company had experienced a delay in ramping up operations and could not line up investors to build a factory.

"It certainly did not help that hundred of millions in DOE stimulus funds went to two Korean companies and one French company, Saft," wrote Neal Maguire, vice president of business development."

Imara employed 38 scientists and engineers and will be attempting to sell its assets and IP.